|

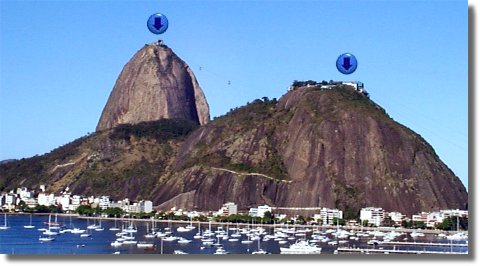

| Pão do Açúcar (left) looming above Morro da Urca (right) |

We step out of the cable car with dozens of other tourists, on top of Pão do Açúcar, the Sugarloaf Mountain. Pão do Açúcar is a sheer rock outcropping, about 1,000 feet tall, that emerges from the surf where the harbor of Rio de Janeiro meets the open sea. Copacabana and Ipanema beaches curve off to our left. The South Atlantic smashes against the rocks down to our right. Behind us lies downtown Rio, the fancy hotels along the beaches, the slums on the mountainsides, the city stretching on as far as the eye can see, broken only by steep mountains, abruptly poking out in the middle of the city.

Standing on top of Pão do Açúcar must once have been spectacular. Then the cable car was built, and it became too easy -- a nice day trip for the family, and the most popular tourist destination in Rio. "Look at all these tourists," I complain to my Brazilian buddy Marcelo. "We have to climb it," I say provocatively, "or it's nothing more than visiting a picturesque gift shop." Marcelo ignores me. "Let's walk down to the bird park; you'll like the birds and the view," he says. "I want to climb down. The cable car made me nauseous and the crowd was suffocating." "We can't make it by dark," he says, "It's a very long climb." Like a good Carioca, Marcelo's hobby is mountain climbing, so I assume that he knows best. I try to look past the screaming kids and their sunglassed, sunburnt parents and enjoy what remains of Sugarloaf's beauty. At dusk, we take the cable car down.

A few days later, we climb "Pico do Bico," the Parrot's Beak Mountain. No cable car has been built here, so we are accompanied only by the wind and the vultures. Once we climb above a few hundred feet, the number of vultures multiplies. They nest in cracks in the rock and soar between the mountains. It occurs to me, as I work my way up the mountain, that I prefer their company to that of my fellow species. The vultures have a right to be on the mountain. Hikers earn their place by working their way up. Cable-car tourists do not.

Parrot's Beak is wooded until the very top. On the peak, a 30-foot tall rock sticks out vertically, like a parrot's beak, giving the mountain its name. A rope has been installed on the "beak," to help intrepid hikers reach the summit. From the peak, we survey the city. Pão do Açúcar is visible in the distance. It stands out from the other mountains because its bare rock extends down nearly to the base. "I want to climb Pão do Açúcar," I tell Marcelo again. "It's very hard," he warns me. "You have to use a rope the whole way up. You need special climbing shoes, and a harness, and climbing it requires an entire day." I accept Marcelo's dismissal but I think he's over-dramatizing the difficulty of the hike to enhance the mountain's mystique.

The next Friday I was to leave Brazil. On the way to the airport, I got robbed. I was without a passport until Monday. When we were done cursing the robbers, Marcelo asked, "What do you want to do with your free weekend?" There was only one sure way to keep my mind off of being robbed. "Let's climb Pão do Açúcar."

The trail starts at the sea. The first hour of hiking is like any other mountain in Rio: a steep trail through dense woods. Sometimes you can walk on a trail, sometimes you find yourself crawling more than walking, and sometimes you have to climb the trees. You grab the root of a tree at shoulder level, pull yourself up onto it, and then support yourself on the trunk, while you look for another shoulder-level root.

Then suddenly, the woods end, and a rock face blocks the trail. It continues vertically beyond the line of sight. "Here we are," says Marcelo, "let's suit up." Here?, I think. It's a wall! It's not a mountain, it's a vertical wall! How can anyone climb that? My mouth goes dry. I can't even see the top. The vultures circle around over our heads. He can't be serious; he's just testing my resolve. "Um, Marcelo, where do we actually, uh, you know, climb up?" I ask tentatively. "You can see the rope path from here -- look, where those people are." Arching my neck back, I could indeed see some brightly colored dots halfway up the sheer face. "They must be almost at the top," I offer hopefully. "Oh no," Marcelo answers, "They're at about 60 meters. The top is 300 meters." "Well, that's, uh, let's see, a little over 900 feet, that's not very far at all," I say. Unless it's straight up in the air!, I think.

I had borrowed a pair of hiking shoes with skinny rubber bottoms, thick-palmed gloves with no fingers, and a padded harness, all from one of Marcelo's hiker friends. I was also given a pair of D-shaped clips that attached to the harness. The idea of climbing is that the rope is attached to the mountain, and the rope goes through the hole in the "D", and the D-clips are in turn attached to you. So all you do is pull yourself up the rope, sliding the D-clips along with you.

Marcelo explains to me, "The rope is spiked into the rock every 5 or 10 meters. You keep both clips on the rope until you reach a spike, then you unclip one, and reclip it above the spike. After it is secure, you unclip and reclip the other. That way, if anything goes wrong, there is always one clip attached, and you fall at most 10 meters. To rest, you hang by your harness and support yourself with your legs against the rock. To climb, you hang on the harness and walk up on your legs. You cannot pull yourself up on your arms; you must trust your equipment. I will show you how to use your equipment, but you must trust it. If you can't trust it, we turn around and hike down."

Two climbers walk by as Marcelo shows me the tricks of the trade. I watch them begin their climb. As one guy hammers in a spike, he slips. The rope resounds with a vweep. He falls 15 feet and is dangling in the air; pressed against the wall, his girlfriend supports him by her end of the rope. He swings around and finds a place to right himself, and returns to hammering, seemingly unconcerned. "He could have been killed!" I scream, "How could she hold him up?" "She only has to hold a quarter of his weight, because there are two spikes between them," Marcelo says. "They know that falling is not dangerous if everything is done correctly. They trust their equipment, and they trust each other." I look at the girl, who doesn't look any stronger than me, and at the guy, who's hammering away while trusting his life to her, and I say, "Okay, I'm ready to go."

Our rope consists of a braided steel cable, like the cables that hold up bridges. The cable is attached to a series of spikes already hammered in. We don't do our own hammering, because I'm just a beginner. Marcelo clips onto the first section of cable and climbs up to the next spike. Near the bottom, there are a few 3-inch ledges that one can "stand" on. Marcelo stands on one, ten feet up, while I clip on and pull myself up. I don't really "trust my equipment," but I do trust Marcelo, and he trusts the equipment, so that will do.

|

| View of Pão do Açúcar from the cablecar. |

After reaching the first ledge, it seems pretty easy. I clip on, pull up, clip on to the next one, always two spikes behind Marcelo. The rope weaves back and forth to avoid upside-down sections, so each spike gains only a few meters of altitude. After passing a couple dozen spikes, my arms begin to ache. "Marcelo, I need a rest." "When you get to the next spike, clip on and then just hang there," he says, repeating what he told me at the bottom, but this time it's for real. I clip above the spike and hang on my arms; not very restful, since that's exactly what's aching. "Let go with your arms," Marcelo yells down. "Just hang from the harness. Trust it!" My arms are aching enough that I don't really have a choice. I ease back so that the harness is extended fully, and then gingerly let go. It doesn't break. The blood rushes back into my arms, and my knuckles regain their color for the first time since I left the ground. "Straighten your legs and just relax," Marcelo says, as he hangs non-chalantly on the spike above. I imitate Marcelo's position. After I stop shaking, it becomes relaxing. I avoid looking down.

"How am I doing?," I ask. "Pretty good. We're 30 meters up. There's a cave at 120 meters where you can sit down. Rest whenever you need to." After that, I stop every four or five spikes to relax. I get used to hanging, and actually build up the courage to look down. There are vultures below, circling around in the air currents. The wind feels nice, as I'm sweating heavily. The only sound I hear is Marcelo's footsteps up above. I continue upward, slowly. Eventually Marcelo shouts down, "I'm at the cave."

The "cave" is more of a large horizontal crack in the rock than a cave. I can lie down, sort of, but I leave a clip on the cable, because if I roll over the wrong way, it's the edge. Marcelo dangles his feet over the precipice. I huddle as far to the back as the harness will let me. I ask for a review of climbing techniques, less theoretical now than at the bottom. "It gets easier above here, because it stops being vertical. It's easier to walk with your legs the less steep it gets," Marcelo concludes.

We leave the cave after half an hour, with me now feeling like an experienced climber. I clip on, and climb with my legs instead of my arms, as Marcelo had instructed. It really is much easier that way, and my arms no longer throb. I hang freely from time to time, more accustomed to having hundreds of feet of air beneath me. The steel rope has little barbs, ready to poke through my gloves and my skin. Now that my muscles aren't aching so much, I notice that my fingers are bleeding. Nevertheless, I feel good. I'm not gonna get killed doing this.

Above the cave, the tourists' cable car comes into sight. Every ten minutes, a carload hums by in the distance. As we climb, it draws closer. The tourists can see us from the front window, and I wonder if any of them wish that they were climbing instead of riding. I wave as each car passes.

As I clip on to the next spike, I feel the D-clip unclipping from my harness instead of from the rope. I find myself with a free D-clip in my right hand, with the cable in my left hand, and with the other D-clip below the spike. I fumble to get the D-clip back onto my harness, but I can't manage it with one hand. I decide I'd better try to clip the other D-clip above the spike, so that I can use two hands. That would mean being supported with only my left arm. Well, it's only for a second. It's okay, I figure. I unclip the second D-clip with my right hand, and try to pull up with my left arm enough to clip above the spike. But my left arm has gotten tired from all of the fumbling, and I can't lift myself. "Marcelo...," I yell, "I'm stuck here...." He surmises the situation immediately, and calmly but forcefully instructs me, "Put the first D-clip into your pocket to free your right hand. Pull tight on the harness to gain a little length. Now, pull up hard for a few seconds, and then you can relax all you need. Pull, now." My left arm is trembling from muscle overuse, but I know that I must force it. Focusing all of my strength into my left arm, I pull as hard as I can. My biceps and forearm feel like they're ready to explode, but I get the clip on. I breathe a huge sigh of relief. I let go. I hang from the spike, trembling all over. Marcelo climbs down to one spike above me and says, "Just relax now. You were in trouble there." I massage my left arm until it's back to normal. I clip on the second D-ring. I start climbing so Marcelo can see I'm back to normal.

We proceed up the rest of the spikes until I can see the cable-car dock, a huge concrete block looming over our heads. By now, the slope has diminished to 45°. "We're finished when we get to the cable terminal," Marcelo tells me. "We walk with the tourists from there." We still clip on, although it seems somewhat perfunctory, since 45° isn't steep enough to fall down, it seems. Fifty feet from the top, Marcelo unclips and scrambles to the concrete sidewalk. I notice that the rope ends where he unclipped. "Uh, Marcelo, the, uh, the rope...," I yell up, suddenly feeling that clipping on is not at all perfunctory, but entirely necessary. "They don't want tourists to get any ideas about climbing down," he shouts. "Sorry, I forgot to tell you." Somehow "forgot" seems like an insufficient justification, I think as I unclip from the last spike.

Marcelo pulls me up onto the sidewalk at the last step. Laughing, we embrace. "Yahoo! We made it!", I scream. "You have climbed Pão do Açúcar. Congratulations," Marcelo tells me. We walk, horizontally, to the cable car terminal base. We pass a guard with a machine gun, who doesn't know quite what to do when we arrive from beneath him. He lets us by, despite the sign forbidding passage beyond that point. We arrive at the cable-car, and mingle in with the tourists. They no longer seem out of place: they're now people who I'm happy to be among. We sit down at a cafe, with bloody hands and beaming faces, dripping sweat and jangling harnesses, and order a coconut juice. After four or five coconuts apiece, we take the cable car down.

"Hey, Matt, I climbed a rock wall in Brazil," I tell my mountain-climber friend when I get home. "How high?," he asks, ready to be unimpressed. "900 feet." "900 feet?! Nine hundred? The most I've ever done is sixty! 900 feet is not for beginners!," he says. I can only respond, "Well, it's a good thing I didn't know that!"

|

| Thanks to Bondinho do Pão do Açúcar for the pix! |

| Article Index | About Instant Web Page | About WebMerchants | Next Article |